The curatorial and editorial project for systems, non-

Interview with Eric Butcher, by Karen Loader

January 2020

©Copyright Patrick Morrissey and Clive Hancock All rights reserved.

KL: Firstly, I’d like to say how much I enjoyed seeing your latest solo show at Patrick Heide Contemporary Art. It was my first encounter with your work so I have a lot of questions regarding the work itself, your process and how it relates to philosophy which you studied at Cambridge.

KL: To begin, I wanted to ask about the title of the exhibition -

EB: I think I just made it up. It’s not a big deal to be honest. I find titles a

bit arbitrary which is why I title my work with reference numbers. It’s a pretty

systematic way of titling and I really think I should title my shows in the same

way, just give them reference numbers, but I guess that’s not very interesting. The

title is really because I feel that what I do is quite peripheral and that a certain

sort of work, mainly issues-

P/R 730. (2016) Oil and resin on aluminium. 108 x 158 cm

KL: Your process of making is very intriguing. I love the way you build up transparent veils of colour, combining vertical lines with horizontal ones in some of the pieces. In this way it appears to reference the grid and Minimalism, but also the warp and weft of weaving. Is there any acknowledgement of design in your work?

EB: It’s not a conscious reference to anything really. Most of the characteristics of my work are things that have evolved organically through the process of making over the years and so if there’s a grid it might be because it’s seeped in from somewhere, from things that I look at or the stuff that’s around us. The end result, the painted surface, is driven these days by a more loose set of procedures. In the past they were more rigorous and narrow. One of the things I wanted to get across in the show is how the process I use has widened and expanded over the last few years, so there are a number of works that show a much wider range of applications.

KL: What is the span of works in the show?

EB: About four years. But most of the works are from the last couple of years with a concentration from the last year.

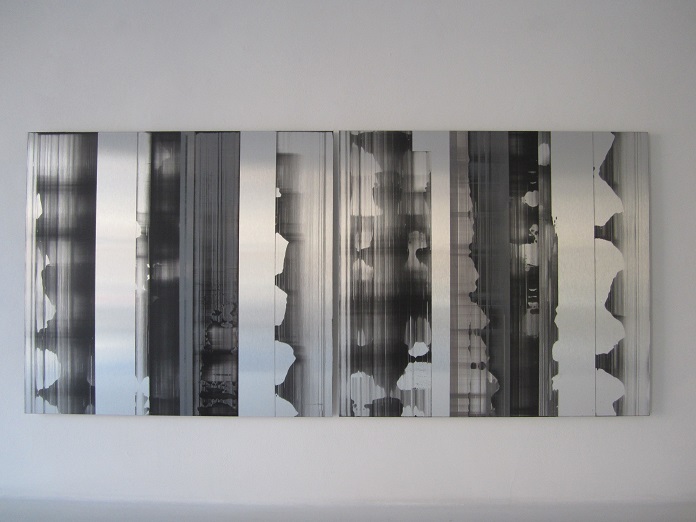

Gallery installation shot of framed works on paper

KL: The works on paper are framed and hung as a series in a grid format and are one of the first things you see when entering the exhibition. I like the way they set up a dialogue with each other but also with the surrounding paintings.

EB: Yes, that first wall of paper pieces is quite a nice tuning fork for the show. Despite the fact that all of those were done in the last year, it shows pretty much all the creative concerns that manifest themselves in various different ways throughout the show.

KL: Some of the things you do with the works on paper are quite incongruous, like using screws and bolts and bits of metal. Can you tell me a bit more about this?

EB: These things start off in various different ways as diagrams, studies or research. They have that typical characteristic of drawing, of ‘visual thinking’, but then they evolve into finished objects. Much of the visual thinking that goes into the painted aluminium works occurs in the paper pieces. They get made in short sporadic series, so it’s quite interesting for me to bring them all together and survey what’s been going on over a longer period. There are lots of different threads of enquiry that wind their way through these pieces.

As far as the metal inclusions are concerned, they are means by which the pieces are held together. The manner of physically constructing a work of art, or hanging it on the wall or holding it together is, for me, a fundamental part of it, not something ancillary or incidental. I want these physical means to be evident, open and honest, not hidden.

KL: In the paper works is there some kind of printing process that you use?

EB: Yes, some of them are blind embossed and these things started off when I was making, am still making, large scale installations of painted aluminium sections. To work out the ‘composition’ for these I take a series of shards or offcuts of aluminium and throw them onto an etching press. Then they get run through the press with a piece of paper over the top so you get a heavy emboss of these geometric shapes. I then repeat that process two or three times and where the embossed shapes intersect I cut them out. Sometimes, one or a number of plates are inked up and so it’s partly a monoprinting process and partly an embossing process. But they started off as diagrams for where I should place the painted aluminium sections in the installations and then evolved into something else. They’ve become an intrinsic part of other processes, other paper works. So a lot of the other paper works have an element of embossing in them. I remember when I started printmaking, when I was 16 or 17, that first moment when you pull the damp paper off the plate and see what you’ve got, it was less about what was printed on the plate but just the brute fact that there was this object, the presence of which is implicit in the trace of what is left.

G/R. 593 (2003) Ink on blind embossed paper with cut-

KL: There’s a trace and also the surprise element or the chance occurrence of the printing process?

EB: Yes, chance is very much one of the things that attracts me to printing processes.

KL: I wanted to ask you a bit more about chance and order in your work. Your finished pieces look quite slick, well finished and hard edged but they also have a tactile quality and are quite sensual.

EB: For me it’s all about tension. I have always been attracted to art, particularly painting, that is imbued with tension. In my work, one of the great tensions, one of the things I look for, is between order and chance. It’s one of several preoccupations in the work, but one that I’m particularly interested in; between control and chance and the possibilities of navigating the tension between those two. It’s not something you can formulate. It’s something you manage or negotiate.

KL: Presumably it comes from the experience of making and through repetition? I imagine that when you are repeating the same processes over and over you come to realise what is possible?

EB: Yes, and what’s fruitful. I’ve been doing more or less the same thing for the last twenty years. I go to the studio. I take oil paint and mix it with resin or graphite with acrylic gel or more recently acrylic paint as well and I squeegee it across a surface and then strip it off.

KL: Using a printmaking squeegee?

EB: No, they’re aluminium blades, although more recently I’ve been using window cleaning squeegees.

So for the last twenty years I’ve basically been doing the same kind of thing and it’s all about that incremental and slow evolution of the process, through the inclusion of chance occurrences and the building up of the experience of knowing what’s a good occurrence and what’s not and that’s just something you learn through experience. Which are the useful avenues to go down and which are blind alleys?

Another thing that’s become quite important recently, is that the blades I’m using

to squeegee the paint on and strip it off start to change over time. So you get a

build-

There are a number of different things going on in each painted surface, partly to

do with the nature of the support, partly to do with the nature of my movement across

it and more recently the nature of the stripping tool and the way in which that has

evolved over time becomes manifest in the finished painted layer. It’s become much

more self-

KL: Your choice of aluminium as a support transforms the paintings into objects. For me the finished pieces hover somewhere between painting and sculpture.

EB: That’s another of those tensions that I find really engaging; the relationship between a flat painted surface and the acknowledgement that it’s only one surface of an object, and although it’s one that is not fully three dimensional it still has sides and still hovers off the wall and there’s a relationship between the painted surface and unpainted surfaces.

P/R. 726 (2016) Oil and resin on aluminium. 108 x 118 cm

KL: In the exhibition there are quite a few pieces where you’ve juxtaposed the painted aluminium sections with the unpainted aluminium. What is the reason for this?

EB: I started doing that a long time ago when I was doing flat paintings in series; so you’d have a painting comprised of maybe four or six plates and I’d include one blank plate, almost like a control in a scientific experiment, to show what the surface actually is because one of the things that I’m doing is exploiting or amplifying characteristics of the support that aren’t obvious or visible to the naked eye. Having one plate that was unpainted seemed to make sense so you’ve got something to compare the painted plates with. And there’s obviously also a compositional implication to that.

KL: And there’s also the relationship between the painted section, the unpainted section and the wall?

EB: Yes. The spaces between them are important, the relationship between the size of the wall and the size of the plate and the size of the gap between the plates. They’re rather modernist, formal concerns and of course that’s not all there is to the work, nevertheless I spend quite a lot of time thinking about these things.

Installation shot of I/R. 882. (2019) Oil and resin on aluminium block. 100 pieces,

10 x 10 x 2.5 cm each (60-

KL: I’d like to ask you a bit more about the installations. The piece in the show that is hung as you go up and around the staircase leads the viewer up and around and forces you to look up and down and from side to side and I wondered how you see that engagement with encouraging the viewer to respond to the work in a physical way?

EB: Once you start to consider the painted surface as just one surface of a three-

Going back to the embossed pieces being diagrams for the large installations, what that’s giving me is one element of the ‘design’. When it comes to installing the work I’ll make changes to the diagram based on all those things we’ve been talking about; the viewer’s interaction with the space, the type of space it is, the light source and so on.

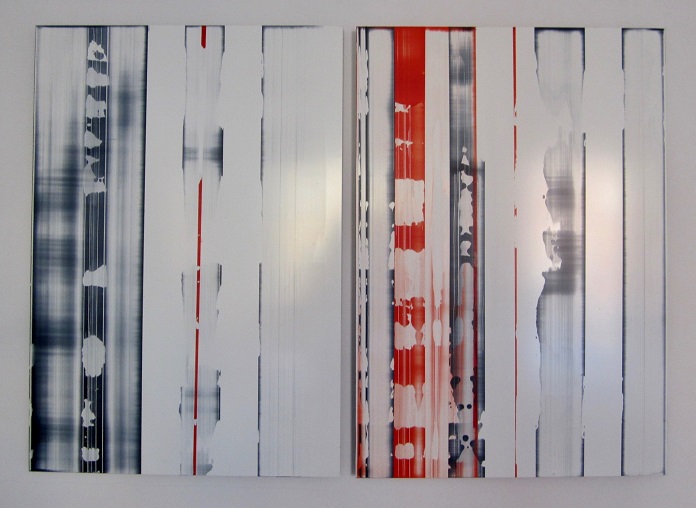

E/R. 884 and 894 (2019-

KL: And also the architectural features of the space like the small pieces where you’ve split them in two either side of a pillar or beam? It draws your attention not only to the work but to the space itself and its architecture. Generally, I find your work quite architectural and urban, which is strange given you live in the middle of a forest.

EB: Architecture is something I find fascinating. I work with architects quite a

lot doing site-

KL: Your work also makes me think of the Light and Space movement in Los Angeles in the 1960’s and in particular the work of Robert Irwin? I don’t know if you’re familiar with his work, but he makes large scale installations that explore ideas of perception and how you can make people see things in a different way. This links in with phenomenology and philosophy and I wanted to ask you if studying philosophy has shaped your work in any particular way and if there are any philosophers in particular who have influenced you?

EB: That’s a really tricky question and one that I don’t have a very satisfactory

answer to. One of the things I learnt from studying philosophy is simply how to look

at things in a different way, from different perspectives, but another was intellectual

humility. I met some extremely clever people who were intellectually very impressive.

I think one of the reasons I sometimes struggle with issues-

KL: Yes, I’m a bit of a magpie myself. It is what some artists do. They will take things from different aspects of life or different philosophies and then combine them in a new way which in turn creates a new experience. And that’s what artists put out there.

EB: I think that’s right. It’s about the creation of an experience rather than the contribution to a debate. There’s very little real content, but that’s not necessarily a criticism. Making somebody think about things in a different way or look at things in a different way has great value. I just think there is sometimes a tendency to always seek out an intellectual justification for a body of work. What we’re creating are experiences and not generally intellectual content. It’s a different thing. So much art I see appears to be trying to illustrate other people’s ideas, some theory or other. Time was when artists used to do things and theorists would then try to make sense of them afterwards. Now artists seem to have relegated themselves to intellectual illustration.

Going back to the philosophy thing there are certainly lots of philosophers who I admired and got a huge amount out of but whether that feeds into my work I don’t really know. People like that would be Wittgenstein, Nietzsche and David Hume. They’ve been influential in my life but whether it influences my work directly I’m not sure. Nietzsche perhaps would be the most obvious connection I guess.

KL: I find in my own practice I have been quite influenced by reading Maurice Merleau-

EB: One of the things that’s been occupying me a lot over the last few years is

the way in which I think my work is deterministic (and so this connects with what

you’ve been saying). So much of what I do is a consequence of or a function of things

that I’m interested in, because of reading things, or just characteristics about

my physical self, my body, my interests which are maybe nothing to do with art. So

I think in a kind of intellectual way or in more of a conscious way I’ve been trying

to think about and to some extent take away elements of decision-

I often talk about the relationship between sport and my work. But because I do a lot of sport, it doesn’t mean it’s manifested in my work, but the systems and processes involved are not dissimilar. The idea, for example, in many sports of perfecting a rather simple action and habituating that action to achieve results you couldn’t have achieved by an intellectualised action. The idea that something more profound occurs when the cognitive faculties are bypassed.

KL: It’s almost like building up a muscle memory which is what happens when you repeat a process?

EB: Yes, it happens in sport and it happens in lots of other walks in life as well. I try to exploit these processes.

P/R. 850 (2018). Graphite and acrylic gel on aluminium. 56.5 x 62 cm each

KL: It’s interesting you mention sport, because I see there’s a lot of movement in your work. It moves in and out and up and down and from side to side and it also travels.

EB: And there’s a physicality to it.

KL: There’s also a sense of time passing. When I first saw your work I couldn’t help thinking of cinema and photography and the idea of a negative spooling through an old Steenbeck machine, being spliced and put together again by hand.

EB: I think that’s partly because that’s how they’re made. It’s completely unconscious

but actually they are made in a very similar way and there is something about the

rhythm of making, which is determined in part by the physicality of my body, my reach.

But also these are made up of cut up sections which are then re-

P/R. 886 (2019) Oil and resin on aluminium composite board. 57.5 x 40 cm each.

KL: So that is a similar process then. It is particularly so with the pieces that have fewer straight lines, but more of a smudgy line. I guess a more contemporary analogy would be a screen swipe or like when you’re on a train and the countryside passes by but it all starts to merge and blur like it’s speeded up.

EB: Again, these are not things that I’m consciously reflecting on or referencing in the work, but perhaps it’s not surprising they remind you of those things because of the manner of their construction. The more organic pieces you were talking about look quite different. Despite the fact that they are made in an almost identical way they are made with a different tool. They are made with a window cleaning squeegee and because it’s rubber and I’m using a thicker more viscous material it takes and then doesn’t take and then takes again and I’ve consciously encouraged that. It occurred again by chance and to start with, I thought that’s not at all what I was after, but then I thought there’s something in that and it’s more interesting than what I was after. And very often it’s about having the openness to acknowledge when something is not what you were looking for but is actually more interesting and has more potential.

KL: So, it can start off as an experiment and then lead to something new?

EB: Yes, almost every development that has occurred in my work has been started by a mistake. So it’s sort of an amalgamation of twenty years’ worth of mistakes I guess. I often talk about ‘error’ and the fruitfulness of making mistakes and learning from them and sometimes realising that what you wanted to achieve isn’t necessarily worth achieving in the first place. It’s the identification and the sifting process I think that is interesting. Because you get things wrong all the time but it’s acknowledging which ones are potentially useful or fruitful.

KL: Do you find you ever get ahead of yourself? You might find you do something and then make a big leap or is it a much more gradual development?

EB: No, the big leaps occur. I like to think it’s always completely gradual but some leaps are bigger than others.

The other thing that’s been happening quite a lot recently is that I’m back tracking or revisiting earlier work and previous issues. I hate to give the impression that it’s all progress. It’s just going round and round in circles really. I keep a lot of old work around, things that have gone wrong sometimes. There might be work that’s lying about the studio for ten years before I work out a way of using it, or they might suggest a solution to a problem I’m wrestling with now.

So, the piece in the exhibition going up the stairs is a different iteration of a

previous piece of painted blocks which I used for a floor-

P/R. 770 (2017) Oil, resin, graphite and acrylic gel on aluminium composite board. 124 x 90 cm.

KL: There’s something rather nice about that. It’s a bit less precious and it’s more about you as the artist and less about worrying how it’s going to be seen or received.

EB: It feels a great privilege to be able to pursue one’s creative inclinations wherever they might go. I’d hate to feel inhibited by that and the need to produce x y or z.

KL: When you’re asked to do a commission do you find that more inhibiting?

EB: I’ve made some mistakes in the past. I think I suffered a little from an over-

KL: And sometimes there can be too many people involved in the decision making?

EB: You mean ‘design by committee’? In a way I’m quite lucky in that the way I work

is quite old-

KL: And holding on to your own integrity is really important isn’t it? Not getting sucked into something that’s too big and not repeating yourself over and over again for the sake of it.

EB: Well, repetition is an almost fundamental part of what I do. It’s just that it evolves very slowly into something else, so when I look at the work I’m doing now and the work I did ten or even twenty years ago, in spite of the fact I feel like I’ve been doing pretty much the same thing every day with some minor tweaks and fiddles, the actual result is quite different.

KL: It’s a bit like you said earlier about scientific experiments. Like you’re asking yourself what happens if I do this? What happens if I tweak this or change that colour band?

EB: I think the science analogy is a really good one. I’m not a scientist, I don’t know very much about science (in spite of having studied scientific methodology), but this idea that in an experiment you need a control, you need to keep everything the same and just change one small thing. Otherwise, it’s just a mess of data. And from a procedural point of view that’s what I do. I just change one small part of the system. Hence the incremental progression.

KL: That’s also why your work looks so consistent and why it has such a strong identity. It looks like your work. You would immediately recognise a piece as being yours. The rigour behind it is what makes it so strong.

EB: You can’t change everything, otherwise you don’t know where you are. When I was painting on curved structures it would change depending on the ambient temperature and whether it was summer or winter, just because the fluid was more fluid in summer because it was warmer and I love the way in which the environment alters the way in which you work.

KL: That’s the chance element again. Sometimes things are beyond your control. It’s always a balance isn’t it between the perfect and the imperfect?

EB: Again, it’s about tension isn’t it? These things pull against each other.

KL: Yes, there are a lot of binaries involved, a lot of opposites.

EB: I think that’s one of the things I’ve always been attracted to in other people’s work. I am naturally drawn to this friction between different opposites and it’s the friction or tension that’s the engaging bit.

KL: That sounds like very sculptural terminology to me. I studied sculpture and those questions come up a lot and I recognise that in your work.

But I’d like to move on to the question of colour. In a way, your use of colour is what makes your work identify more with painting and I wondered if your choice of colour comes from anywhere in particular?

EB: Good question. There is a system of sorts. So, largely speaking, the first colour

I use is the last colour I used on a previous piece. What I don’t want to do is randomly

choose a colour. I don’t want to get into that intuitive thing of ‘I’m going to paint

in blue because I’m feeling blue’. Not wanting to waste the pot of paint I’d just

mixed up with resin, I found myself almost naturally, starting with that one. And

it just became a thing. So the first layer of paint is one that is determined by

a previous choice, so then that begs the question what’s the principle by which that

develops? I think it’s partly a formal thing. I’ve got one colour down, what do I

want to do with that colour? How do I want to respond to it? And depending what I’m

painting there are lots of different possible drivers in terms of decision making.

I often wonder if I’m influenced by the things around me. I live in nature, so does

that have an effect? I suspect it does, although it’s not an intentional one. Also,

I have found myself using found colour relationships in the past, colour relationships

that I’ve seen in packaging, say. When my daughter was very little there was a programme

called In the Night Garden -

KL: So it can be a combination of observation and things that you pick up along the way and then responding to something? It’s a bit like with form and line. You put down one line and then have to respond to it in some way?

EB: Yes, or whatever that starting point is.

P/R. 818 (2017-

EB: I find that the palette I use evolves over time. There are periods when I’ve been using one particular colour or a certain type of colour relationship or a narrow restricted palette. And then some months later it’s moved off in a different direction. And one of the interesting things about having a solo show is that you bring all these different works from different series together and think ‘actually those work well together’ or you might find you’re revisiting a palette you visited years previously. It’s another example of how things don’t really progress, they just go round and round in circles. Maybe the third time you visit this set of creative concerns you have a different solution because you’re a different person.

KL: I often find in my own work, without consciously doing it, that my colour choices are influenced by the seasons. For example, in the winter they often get darker or more subdued.

EB: Do you think that’s because of your experience of nature or your environment or is it something else to do with winter? Is it because it’s cold, say, or because you’re inside all the time?

KL: I think it comes back to that idea of experiencing. How we experience our environment and our surroundings and that we are always unconsciously absorbing stuff and like you said earlier, how things filter through. You absorb things visually but also physically with your whole body through all your senses. So, for me the idea of rhythmic experience is quite important because it’s something you feel with your body rather than see with your eyes.

EB: Yes. And the visual ones in a sense are quite superficial and sort of a bit obvious. Whereas the more experiential influences might have a visual manifestation but they’ve come from a different route.

KL: And they somehow sit more deeply within you. It’s similar to our experience of space. How we sense different types of spaces in different ways. There can be open spaces or restricted spaces. It’s about the way that space can expand or contract depending on where you are and what you’re experiencing. And I picked up on that in your work.

EB: For sure. There’s a tendency when talking about work to over simplify it for the ease of consumption. Actually there isn’t one answer to a question. There’s a whole host of different things going on. On different days or different times of day or different times of the year certain things come into dominance and they recede later on in the year or day. So quite often when artists talk about their work it sounds like gobbledygook to other people. It’s because there is this tendency these days to have to have a research principle for your work that is clear and differentiated and that progresses through time. And actually most artists’ practices are far more complicated than that and it’s much more like a prism. You need to look at it from different sides because there’s a lot of different and contradictory things going on. And at different times different things have dominance. If you were to write a statement about your work every day for a year and be honest about it, it would probably be quite different at different times and they would all be true.

KL: I agree, it is very complex and it is hard to speak about your work in a concise way.

EB: And you want to do the complexity of your practice justice and you don’t want to over simplify it for the sake of making it easy to consume.

KL: Yes, absolutely. I think that’s a good point to end on. Eric, thank you so much for agreeing to talk to me today.

G/R. 594 (2003) Ink on blind embossed paper with cut-